You are here

Chapter 5

THROUGHOUT THE MONTHS Camp Greene was located in Charlotte, the men were overwhelmed with displays of hospitality. During the cold winter and flu epidemic, the townspeople supplied the men with wood, medical necessities, blankets, clothes, knitted goods and an ample supply from the ladies of the Queen City of "old-fashioned mothering." The patriotic enthusiasm of Charlotteans for the camp was best expressed by the following greeting from Mayor McNinch:

Charlotte holds it not a favor or even a duty, but a privilege to open her gates and welcome in the heartiest and sincere fashion possible these men who wear the khaki - the insignia of the American nobility. We are fully sensible of the honor that is ours in having as our guests a part of the American army, the very promise of whose going "over there" is a sign of deliverance set in the heavens, to which an oppressed world is looking with a hope and faith that shall be justified by the sacrifice and service of these men. For they have caught the uplifting vision of America's mission and set their faces towards the war-torn fields of France, there to hurl freedom's thunderbolt of light and right against Autocracy's fronting hosts of might and right.

One and all we welcome them as soldiers and as men - we care not whether they hail from North or South, from East or West; for though once we met in the strife of civil war, now, happily, we march one way, worship at one common shrine of liberty, pledged to a common defense of

"Your flag and my flag, the red, white and blue."

For what they are, for the exalted mission on which they come, for the hope they bring us and to the world, of peace through liberty and democracy, we bid them welcome to our city, our hearts, our homes, and we hope by our deeds to seal the sincerity of our words.

When soldiers arrived at the railway station, they were greeted by ladies with doughnuts and sandwiches. The soldiers felt the sincerity of the mayor's words with their first impression of Charlotte.

Troops from the North discovered there was more than a physical adjustment to life in the Army; they faced a tremendous cultural adjustment at Camp Greene. These men were not accustomed to the "provincial" attitudes of Southerners. For example, "closed Sundays" were maintained at the insistence of the preachers and religious leaders of the city. An appeal was made to the people of Charlotte to meet the soldiers halfway. The men said they realized they "must appear as animals of unknown instincts, but after a hard week of training, weren't they entitled to some relaxation?" It was hastily added that they did not seek vulgar or "sordid" play, but only the chance to enjoy themselves and the pleasures of Charlotte on Sundays. They were aware of the "restrained and sedate" mannerisms of Southerners, and reminded the townspeople they would attend churches regularly and conduct themselves as gentlemen at all times. They accused the ministers of Charlotte of sermons telling young ladies to fear and avoid all social interaction with uniformed men. The following appeared in the camp newspaper:

They're So Rare

The lass we doff our chapeau to

Is Little Sarah Form

She doesn't have a duck fit

When she sees a uniform!

M.T.

In desperation, the soldiers threatened to boycott "everything that pertained to Charlotte and North Carolina." The problem was obviously a major one to the men. If allowed to go unresolved, it could have led to strained relations between the townspeople and the soldiers. To avoid this, the Fosdick Commission on training camps and activities was set up and proved to be the most important factor in maintaining congenial relations. The Commission consisted of several sub-divisions dealing with sundry matters.

As soon as the Commission was organized, W. A. Wheatley, a War Department representative, assisted the community in developing its own resources for the welfare of the men. He compiled information concerning what other cities had done for the soldiers stationed near them, and applied these suggestions to the local situation. Various religious, social and civic organizations of the city as well as the committees of the Charlotte Commission benefitted from Wheatley's aid.

One of the first matters undertaken by the Commission was the providing of adequate rest rooms for the soldiers when they were in town on leave. The Accommodations Committee (W. H. Peeps, Chairman) met this need through the generous cooperation of the downtown churches. Nine of the churches converted parts of the Sunday School buildings into soldiers' rooms, with facilities for reading, writing and lounging. Several of the churches provided outdoor benches on their lawns.

Complete lists of available boardinghouses in the city were compiled by the Chamber of Commerce and the YMCA at the request of the Information Committee of the Commission. The lists were of great value to the relatives and friends of the soldiers. Also under the direction of the Information Committee, census cards were distributed to the soldiers at Camp Greene. Each man was asked for information concerning church preference, membership in fraternal organizations and previous business or profession. The cards were turned into the general office and the information proved valuable to the community. The townspeople used this file for a variety of reasons, such as selecting guests for dinner and making invitation lists for parties.

In one month, the Commission's secretary had 157 private conferences to obtain suggestions from the men. Ideas included the type of entertainment desired, church socials, additions to the soldiers' rooms, band concerts, community sings, gambling machines, care for the Negro troops and many others. Approximately 500 messages were acted upon in some way.

A helpful feature of the Commission's general office was a bulletin of spare time activities for soldiers issued every Wednesday and posted in soldiers' rooms throughout the city. The men learned what activities were available and where they would be held. Often names of people in Charlotte willing to entertain in their homes were listed. Individuals and organizations who wished to invite soldiers or military units to social affairs or meals contacted Mr. Wheatley, who notified the various men. Citizens in the suburbs and neighboring towns (especially Mount Holly) used this method to invite soldiers to Sunday dinner. On several Sundays the number of invitations numbered between two and four thousand.

Another phase of the work of the Commission was the arrangement of certain groups of soldiers to entertain Charlotteans. Soldiers entertained numerous social gatherings. In some cases the Commission managed to get automobiles for the transportation of soldiers to and from town for the performances. These activities contributed greatly to the good rapport between the men at camp and the townspeople. The Commission was also responsible for arranging popular community sings.

The number of soldiers attending church services was considerable. One prominent citizen commented, "The soldiers a burden? Why, as a matter of fact, they more than pay their way at our church. The Sunday collection has averaged an increase of twenty dollars every week since the soldiers came." After services soldiers received spontaneous invitations for home-cooked meals and pleasant afternoons around the piano singing "Back Home in Indiana." This story was told by a British captain of what happened at a dinner in the home of some townspeople:

There was an elderly lady of trim and severe appearance seated at his right, and a charming young lady was on his left. The captain started discussing with the young lady the merits of motor cars. "What color is your body?" asked the captain of the young girl at his side. "Oh, mine is pink. What is yours?" "Mine," replied the captain, "is yellow with brown stripes." This was too much for the old lady. Rising from the table, she exclaimed, "When you young come to asking each other the color of your bodies at a Charlotte dinner party, it is time I left the room!"

Strong friendships developed from these experiences, and for years some of the men kept up a regular correspondence. Charlotte citizens received many letters from the parents of the men thanking them for the many personal kindnesses.

Another important part of the Commission's work was the effort to maintain a proper moral environment in the city. Emphasis was placed on religion to steer soldiers clear of the "evils" tempting them. Although off limits, the many saloons in Charlotte were frequently visited by Camp Greene soldiers. It was a time when bootleggers got rich. The boys would drink anything they could find -- shoe polish in some cases! One place frequented was Johnny Clements, a tobacco shop with a poolroom in the back. Usually a whole shelf of the soldiers' "private stock" was ready for the next leave. When a military policeman approached, Johnny would warn the soldiers saying, "He's a dick!" The men quickly closed off the area and continued their pool game and conversation until he passed. The soldiers poked fun at one officer who claimed to have made a very thorough search of Charlotte and reported the city completely void of alcohol. "We have all faith in Doc," they said, "but we doubt if he has the same scent for liquor as some of us!"

A proper moral climate was seen as necessary, not only for the soldiers but also for the protection of civilians -- especially the women. The Commission did not bother much with movie theaters, dancing places and pool rooms as these places were generally well-supervised. Some concern was expressed when reports surfaced of women making "assignations with soldiers within the camp limits." Chief Elliott of the military police received complaints from parents of their daughters visiting the camp at late hours. (Women were prohibited from visiting the camp between the hours of retreat and reveille without special permission.) Extra posts were established at the Hostess House on Tuckaseegee Road, at the streetcar terminal at Camp No. 1 and at Liberty and Lakewood Parks. The woods west of Recruit Camp No. 1 were patrolled by military police from 7:00 a.m. to 9:00 P.M.

Another concern was the prostitutes (identified as the best-dressed women in town) who roamed the streets of Charlotte. As soon as the camp was built, the military police were sent into town to close up the "houses." Ironically, the houses moved to locations closer to the camp. While the military police continued to patrol in town, it was "business as usual" for the girls.

The work of the Girls' and Women's Committee of the Fosdick Commission, (Mrs. A. T. Summy, Chairman) dealt with the perplexing problems of young girls losing their heads over soldiers. The Committee organized clubs for the girls keeping them occupied in patriotic work and reaching some seven-hundred girls. The Colored YMCA initiated similar clubs. The "creation of a wholesome attitude" of the girls toward the soldiers resulted.

The patriotic fervor of the war effort spread through the country by Liberty Bond drives. Soldiers and Charlotteans alike joined in the crusade for bonds. Many of the men bought bonds on time, paying five dollars out of each paycheck for ten months. Citizens were also urged to buy. Addresses were delivered to inform townspeople about the things soldiers were doing and how the money from the bonds would be used. Movie stars such as Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin visited the Queen City to generate enthusiasm. Charlie Chaplin's stimulating ten-minute speech on April 11, 1918 succeeded in raising twenty to twenty-five thousand dollars in subscriptions. He promised to kiss any woman in the audience who subscribed $5,000 worth of bonds. Although it was a tempting offer, no one could pledge that amount; however, several $1,000 pledges were made. Chaplin spent the morning visiting the soldiers. Shouts of "Hi, Charlie!" "Hoorah for Charlie!" were heard amid cheers as he rode through camp having brief talks with the boys. He visited one company at a mess hall and had a picture taken with the boys circled about him. In the picture, Chaplin holds a plate of dollar bills in place of food, calling attention to the fact that it took money to put something to eat in the soldiers' pans. As he returned to his car, Chaplin assumed his famous waddle. His hat suddenly blew up and, with his familiar expression, he glanced up, reached out and caught it. Charlie was at home with the boys.

The continued activities of the YMCA were always a pleasant diversion for the men. The activities became so popular that more and more funds were required. The townspeople contributed generously and in one campaign raised $19,000. At the end of the first day of soliciting alone some $2,050 was reported by workers; the students at Queens College donated $500 of this total.

Transportation from the camp to the city was increased. Rumors abounded that the fare would be raised from the usual nickel to ten cents each way, but this never happened. Acquiring additional streetcars was a difficult matter. The city managed to purchase secondhand cars needing rebuilding. While the cars were not up-to-date, the men gratefully rode them from the camp to the city.

Private automobiles were given liberty to enter and drive through the area (except on Company Street) without passes after the first months of construction. Between the hours of 4:00 and 7:00 p.m. many curious Charlotteans got a chance to see the camp from the inside and a steady stream of dust-covered traffic passed the Dowd House. Mrs. Lucy Shelby remembers spending a pleasant Sunday afternoon sight-seeing in a sidecar with a young officer - despite the dirt. A speed limit of fifteen miles per hour was enforced by the military. One very amusing incident occurred. A city policeman who was usually assigned the duty of stopping speeders was halted by an Army officer for exceeding the speed limit. Surrounded by amused soldiers, the policeman exclaimed, "I have been coming along here every day. I didn't know there was a 15 m.p.h. speed limit!"

"You'll remember next time," replied the officer, "and so will everybody else!"

Well-chaperoned dances were held regularly on Saturday nights. Young ladies from all over the city attended - from the rich "society" girls with flowing long hair to "Old Fat Lucy" (Miss Lucy Oates), a very popular, jovial hostess who knew and introduced everybody. Generally, a man's rank was important to the girls, and it was considered a successful evening to have danced with an officer. Some dances were held that excluded officers. The following letter from a Charlotte girl to the camp newspaper expresses her feelings about one such event:

Dear Mr. Wetmore:

I really think the dance was a perfectly grand success. I know that I enjoyed myself thoroughly and everyone who was there said exactly the same thing. We all thought that the hall was decorated beautifully with the palms, ferns, and flags. The regimental band played awfully well and the person who was responsible for "camouflaging" it on stage behind the palms certainly had a good deal of artistic taste. At one end of the hall, there was an electric sign which was awfully cleverly arranged. The balcony was filled with onlookers, some of them officers who must have been awfully jealous at not being allowed to dance!

Punch and ice cream were served during the evening and I enjoyed them both!

Everything was fine, music, refreshments and all. The men were awfully nice. The fact is the dance was simply great. Everyone had a wonderful time. All the Charlotte girls were there and quite a number of visitors. I thought that the girls were all prettily gowned and the men seemed to think so too!

All of us hope that the non-coms will give another dance. This is a very short letter of appreciation, but I really haven't got time to write any more.

Sincerely,

Minerva Arrington

Numerous romances of varying degrees of seriousness developed, some resulting in marriage. Charlotte girls were completely enamoured with the soldiers and described them as "the nicest boys anywhere. You never smelled a bit of liquor on any of them." Many mothers had mixed feelings at first, and more than a few were wary of their daughters "taking up" with the men met at these social functions. Some solved the problem simply by accompanying their daughters to the dances and enjoying an evening out themselves!

The soldiers were equally enamoured with the Charlotte ladies. In a tribute to the women in the camp newspaper, the soldiers told of letters from friends in Europe telling of the hospitality of the ladies in France. "We are treated more like lords than soldiers," one said. But for all their enthusiasm "over there," the Camp Greene troops insisted that the French girls could not be more kind and hospitable than those in Charlotte. "Surely no camp has been more fortunate than Camp Greene in having at its doors such a city as Charlotte, with all the charming maids and matrons apparently so anxious to do all within their power to make our stay one of the most memorable adventures of the war."

Charlotteans opened a Community House -- a moderately priced hotel for soldiers and their families. More than forty rooms became available providing relatives of soldiers a place to stay. Transient business was expected to take precedence over regular lodgers, and the hotel provided one large room of cots for soldiers paying a small fee to stay the night in the city.

Charlotte's business boomed with the opening of Camp Greene. At first, near panic arose among a number of citizens regarding the probable increase in the cost of living. A meeting was held by the Merchants Association to discuss the matter. It was unanimously agreed that prices were not to be raised above a reasonable value and no temporary increases would result. Initially, the merchants kept their word; but as time passed, a steady increase in prices appeared in almost every phase of Charlotte's businesses. One man observing the increasing hotel charges, told of being expected to pay $2.50 for a room with the same furnishings that had been $1.50. The price of a hot meal at one store rose sharply from 35¢ to 75¢.

The newspaper advertised daily many "specials" offered to the soldiers, with claims of having the best deal on items from military uniforms to accessories. The men at the camp noticed the change in prices and joked about asking shopkeepers if the merchandise was anything new. "No," said one Charlotte business owner, "we're just relabeling the old things with military names and raising the price fifty percent." Enough comments and real complaints were levied that officers at Camp Greene decided to conduct an investigation into the alleged discrimination of businesses. Belk Brothers, Tate-Brown, and York Brothers stores were examined for charging higher prices to soldiers. Some discrimination was discovered, but not to the extent indicated.

In January 1918, of sixty-three eating places inspected in town, only twenty scored seventy-five or better in health ratings. The restaurants were warned that unless some improvement was made the soldiers would not be allowed to patronize them. A military policeman was stationed at the door of each place receiving scores below seventy-five to prevent soldiers from entering.

The proprietors, influenced by this action, cleaned up their establishments to meet the standard. Charlotte did have many good places to eat. One boy wrote his father:

Dear Dad,

Have been here several weeks now and we are all very much pleased with the town and the people and the folks down here seem to like us. We are treated well everywhere. There is one place in particular that just hits my fancy. It is a lunchroom, soda fountain and cigar store combined, and say Dad, they sure turn out good stuff. They have a colored cook that looks like the "Ham what Am" man and he proudly claims to be the champion cook of North Carolina and I don't believe anybody will challenge it. All the boys in this store go out of their way to please us and make us feel at home. You need not worry about my digestion because the food they serve is all the best and you can believe I am salting down some coin because their prices are very reasonable.

This place is called the Piedmont Cigar Store and Lunchroom, and it's just across the street from that swell big church yard I wrote sis about. I hope they leave us here all winter. I know I will get fat. When you write address it to the above place. It is:

Piedmont Cigar Stores, Co.

201 West Trade

Yours, with love,

BILL

The Charlotte Observer covered every aspect of the soldiers' stay. On Mondays an entire section of the newspaper was devoted to camp activities, and a smaller section was included every other day. The YMCA War Work Council furnished four official pages that appeared in all camp newspapers. The pages contained contributions from the best cartoonists and writers in the country.

The Mud Turtle was the most popular camp newspaper and was published by the soldiers themselves. The articles covered aspects of camp life entertaining to the men, such as editorials expressing approval or displeasure with general camp policies and army life. The Caduceus was another publication organized and distributed by the Medical Corps. The camp newspapers were sold in great numbers on the square to Charlotteans interested in camp happenings - sometimes more interesting than happenings on the Observer's front page.

For recreation soldiers visited two amusement parks on the outskirts of the camp - Liberty Park, an area set up by a private company, and Lakewood Park, which was almost closed by the time the camp was in full swing. There was a small zoo with an ostrich and a bear, and a special area for picnicking. A swimming pool was later opened for the soldiers. Many a warm afternoon was spent by the pool cooling off and trying to socialize with Charlotte girls who "sometimes appeared very clannish at the pool area."

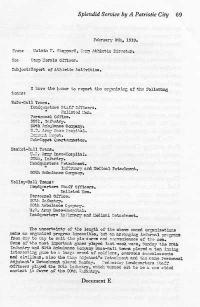

Inter-camp athletics comprised a large portion of the soldiers' spare time. Teams usually matched the men of one regiment against the men of another. Contests for "camp titles" in everything from baseball, football, boxing (at Wearn Field), and volleyball were held. Even mock "World Series Games" were held. Inclement weather did not stop these events; many practice sessions were held by cold, wet players. All these activities were vigorously encouraged for aiding the physical development and confidence of the men.

Musical programs were one of the most popular forms of entertainment. A wide variety of talent and several different bands performed concerts. The soldiers presented programs for the townspeople, and many groups, such as the Shriners, entertained the men. Music was provided for the arrivals and departures of soldiers, and at football game halftimes. Sing-alongs were popular occurrences as well as entertainment by noted opera singers. (Madam Laura Rathbone of Chicago appeared four nights in a row.) Admission was free for men in uniform. Miss Margaret Wilson, daughter of President Wilson, came on May 24, 1918 and entertained the soldiers under the auspices of the YMCA. She enjoyed a pleasant two-day stay at the Selwyn Hotel.

A variety of novelty shows entertained the boys in khaki. Many vaudeville acts such as the Dunbar Vaudeville Troop shows came to the camp. Some of the best vaudeville performances were by the men themselves. Corporal "Kid" Hull of the 38th Infantry became so involved in a show that he forgot himself and began performing on the stage.

Special holidays were exciting occasions. On Thanksgiving soldiers were given liberty for the day. The government provided a turkey dinner, and some of the fortunate companies added their own trimmings. Innumerable basketball, football, soccer, rugby, and handball games were played continually with friendly rivalry abounding. At Christmas, the same care was given to provide exciting festivities for the men. A huge band of seven regiments was on parade, while more than two hundred ladies from Charlotte served refreshments. Wagonloads of cigars, cigarettes and the like were placed in convenient places - all paid for through the generous donations of the people of Charlotte.

The Polack Brothers, a carnival company, set up at Liberty Park making Charlotte their winter quarters. They stocked twenty large attractions. The show carried thirty-two railway cars and represented an outlay of over $250,000 with over 1500 people employed to operate the show at a daily cost of $2500. They aimed to make the troupe the largest and most unique of its kind. As far as the men at Camp Greene were concerned, it was! Amateur circus performances, fair exhibits, contortionists (described as "boneless and jointless"), programs by the Shriners, minstrel shows, checkers championships, stunt nights and barbeques provided amusement for the boys. One of the most popular events was a Wild West Show staged by Captain Lee Caldwell and Troop D at Wearn Field. The soldiers and civilians spent an exciting afternoon watching Caldwell (a champion broncobuster) tame the twenty-five wild horses found among the hundreds at Remount Station.

Not all the soldiers enjoyed such vigorous forms of entertainment, therefore a library was provided for the more sedate types. The American Library Association sponsored the building of a library at all thirty-two United States Army camps. A 120 by 40 foot facility was erected in the center of Camp Greene. The building contained a large reading room, quarters for the librarian, a quiet room for reading, writing and studying, and facilities for 10,000 books. Male librarians were in charge for the most part. Appeals were made for contributions of all kinds of books to fill the shelves. One citizen gave 2237 magazines and 316 books as a gift.

"I shall always remember the few months I spent at Camp Greene," said a captain in the U.S. Army. "I shall aways feel kindly toward the people in Charlotte and I wish it were possible for me to tell them how much finer things are there than where I am now staying."

Other soldiers expressed the same warm feelings due to the hospitality of Charlotteans. Another young man wrote:

The Captain took us to church Sunday and afterwards everyone came and shook hands with us. An old lady asked me to go to dinner with her and the Captain said to go ahead. We had a fine chicken dinner served by a nigger mammy. The old lady had a daughter and they said they would write to you. The people of Charlotte are sure showing us a good time. The lady did write to the young soldier's mother telling of the things Charlotteans were doing to make the boys feel at home. Such kindnesses were typical of the personal attention shown the men at Camp Greene throughout their stay in the Queen City. After the passage of sixty years, almost nothing remains of the physical structure of Camp Greene. However, the camp's impact on Charlotte continued through the years. In the minds of local citizens who experienced the excitement and boom of the era, the camp is more than a fond memory. It provided the city an opportunity to participate in the war effort. But most significantly this was a turning point in the development of the Queen City -- marking the emergence of Charlotte into the industrial New South. It was also a chance to display some 'good ol' Southern hospitality.'

WEtm

Miriam Grace Mitchell and Edward Spaulding Perzel. The Echo of the Bugle Call: Charlotte's Role in World War I. Charlotte, NC: Dowd House Preservation Committee, Citizens for Preservation, 1979.