You are here

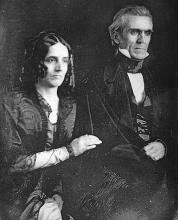

James Knox Polk

James Knox Polk was a native of Mecklenburg County, a graduate of the University of North Carolina, a political leader in the state of Tennessee, and President of the United States.

Although physically small and in frail health as a child, he had a strong will and a retentive mind. These advantages allowed him to make the most of the formal and informal education he received at home and in such schools as existed in Mecklenburg County and in the frontier of Tennessee, to which his family relocated by 1806. The Presbyterians who dominated early Mecklenburg history set great store by the learned professions of the law and the ministry. Young James Polk imbibed that respect for learning. He applied himself to such a degree that when he returned to North Carolina to attend the university at Chapel Hill, he placed into the sophomore class upon entering and graduated with honors in 1818, whereupon he returned to Tennessee.

By 1823 he had earned the right to practice law and was ready to make his first run for office: a seat in the Tennessee legislature. He addressed the task with characteristic thoroughness, canvassing the district to make himself known and eventually overturning the incumbent. He allied himself with General Andrew Jackson, a military hero 28 years his senior. In the same year that Polk was elected to the Tennessee House, Jackson was elected to the state Senate. Polk supported Jackson in every political struggle thereafter and consulted the retired statesman when he himself ascended to the Presidency. (Borneman, pp.15-16)

In 1824, James Polk married Sarah Childress and so acquired what John Adams had considered an indispensable political asset: “a smart wife” (Adams, letter to Abigail Adams, August 11, 1777). Unusually for a woman of her time, she had pursued her education at a boarding school, and so came into marriage prepared to advise and assist her husband. In her public role as hostess she created hospitable environments for political rivals and allies and their wives to meet. (https://www.whitehouse.gov/1600/first-ladies/sarahpolk) The two never had children, and so could work jointly on his career.

Polk served in Congress and also as governor of Tennessee. He remained a Jacksonian through and through, arguing for a limited federal government that was nonetheless sovereign in military matters and in matters of territorial expansion of the United States.

During the presidential campaign year of 1844, North Carolina newspapers filled their pages with stories related to Polk. The Democratic press supported his candidacy while the Whig organs backed Henry Clay of Kentucky. One story of that election year diverted readers’ attention back to Mecklenburg County in the time of the Revolutionary War, fifteen years before Polk was born. What had candidate Polk’s grandfather, Ezekiel Polk, done when Cornwallis marched into Mecklenburg in September of 1780? Polk’s enemies charged that Grandfather Ezekiel had accepted protection from the British general in order to keep his property from being seized. Defenders secured affidavits that he had taken up arms for his country in the early years of the war and then acted as any prudent property-owner would during the brief British occupation of Charlotte. The controversy brought Mecklenburg County’s experience during the Revolutionary War back into the national spotlight, twenty-five years after the Mecklenburg Declaration story spread through the national press.

Polk won the election of 1844, although he carried neither his native state of North Carolina nor his home state of Tennessee. In 1846 he led the nation into war with Mexico over Texas. That war concluded successfully for Polk and the Americans in 1848. Judging that his objectives had been accomplished he stuck to the pledge he had made in his first campaign and declined to run for a second term. (Borneman, pp.113-116, pp.318-319) He never had the chance to develop a post-Presidential career. Typhoid fever took his life in June of 1849, only three months after he left office.

Work cited

Borneman, Walter R. Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America. New York: Random House, 2008.